Just for the hell of it, New Yorkers donned outlandish costumes to dine in fancy “barnyards,” on horseback, amongst swans, dogs and monkeys, and even inside a giant egg.

New Yorkers love to party. Conspicuous consumption is the key. The more outrageous the decor, preposterous the outfits, and exclusive the guest list, the more press attention is attracted. Since the 18th century, news readers around the world have guffawed in amazement at Gotham’s ritzy hi-jinks. Hundreds of thousands of cityfolk starved in decrepit tenements while bejeweled gazillionaires strutted for gawkers along world-famous “Peacock Alley.”

The patent silliness of it all was also available to the lower classes, who could dine in pirate ships, basement “rabbit holes,” and dietetic pill eateries. We’ll tour all of these, so work up an appetite for absurdity and let’s go!

Extravagant Revels

Food on Parade

By 1788, most states had ratified the new U.S. Constitution, ballyhooed by Alexander Hamilton, except for his home state of New York. To promote ratification, a huge parade was held on July 23, featuring the city’s major food industries. To booming cannons and cheering crowds, 6,000 marchers strode down Broadway: the master bakers toted a wagon with a 10-foot “Federal Loaf,” grain merchants and flour inspectors carried the tools of their trades, a butcher’s wagon featured lamb carcasses being split in half, the brewers wore beer foam hats, and confectioners carried a 5-foot diameter chocolate Bacchus cup. The final float was a 27-foot model of a 32-gun frigate at full sail, drawn by ten horses, bearing Mr. Hamilton himself.

Martha J. Lamb, “History of the City of New York,” 1877. (Library of Congress.) (Select to enlarge any image. Phone users: finger-zoom or rotate screen.)

The marchers wound up at a ginormous banquet at Nicholas Bayard’s farm on the lower Bowery. The 6,000 diners sat at ten 440-foot long tables, and devoured a 1,000-pound steer, mutton, ham, lamb, and that big Federal loaf. The food celebration worked: three days later, New York ratified the Constitution.

The Boz Ball

The Food Parade and Feast remained the city’s premier celebratory memory for over 50 years, when its fame was overtaken by the remarkable Boz Ball. The famous Boz (a.k.a. Charles Dickens) was visiting the Big Apple during his first American tour, a suitable occasion to mount the most lavish affair New York had ever seen.

A formal planning committee set the date for Valentine’s Day, 1842, and selected the venue of lower Broadway’s Park Theater, the largest gathering place in the city. The full capacity of 3,000 tickets were sold out almost immediately at $5 a pop, and soon (as is NYC’s continuing custom) were being scalped at $40 each. And, miracle of miracles, even ladies were invited!

The committee intended to outdo, outshine and outspend any event of the kind ever given in America. The stage was extended to cover the entire theater pit, creating a 150-foot ballroom, with a runway for Dickens to make his grand entrance. Thousands of dollars were spent on decorations, including portraits of Dickens characters and American Presidents, elaborate chandeliers, candelabra, flowers, bunting and flags. Scenes from Boz’s novels were performed as tableaux vivants.

The Park Theater (center, white building.) By C. Burton for The New York Mirror, 1830.

And then there was the feasting. Catered by Thomas Downing (see his bio), the “great man of oysters,” the food was prepared by 140 chefs working for 3 days and nights. The crowd consumed 50 hams, 50 beef tongues, 38,000 oysters, and 11,000 candies. The entire evening was brilliantly organized and managed, and the Great Author was duly impressed.

Newspapers throughout the country carried ecstatic descriptions of the Boz Ball, irrevocably cementing its memory into the minds of many Americans for the next 40 years...until an even more impressive event took place.

The Vanderbilt Ball

During the Gilded Age, New York Society was dominated by “old money” (like the Astors.) They never expected that a boy who sailed commuters back and forth between the islands of Staten and Manhattan (before modern ferries were invented) would grow up to become even wealthier than them.

Cornelius Vanderbilt. Daguerrotype, 1850. (Library of Congress)

Nicknamed “The Commodore” due to his boating prowess, Cornelius Vanderbilt soon invested in steamships, then the New York Central, Harlem and Hudson Railroads, eventually building Grand Central Terminal and becoming the wealthiest gent in town. The time was right for his parvenu wife to stake her claim as New York’s ultimate party-maker.

Mrs. Alva Vanderbilt’s fancy dress ball was held in her opulent French chateau at Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street on March 26, 1883. It was the most lavish party the city had ever seen. Of course, the Astors were not invited because they had never visited the “lowly” Vanderbilts. Mrs. Astor had to swallow her pride and drop her visiting card at the Vanderbilt mansion. The Astors received their invitations the following day.

Vanderbilt Mansion. (Library of Congress)

At ten in the evening, carriages began to arrive, delivering 1200 outrageously costumed guests. The gawking crowds had to be held back by police. The wealthy party-goers were decked out in the most elaborate historic finery. Miss Edith Fish came as the Duchess of Burgundy with real sapphires and diamonds studding her gown. Miss Bessie Webb appeared as Mme. Le Diable in a red satin dress adorned with demons. Miss Kate Strong wore a taxidermied cat head and a skirt of cat tails. Dozens of Louis XVIs, King Lears, and Joan of Arcs danced the endless quadrilles.

The center of attention was claimed by Alva Vanderbilt, who attended as “Electric Light,” holding a torch lit by batteries hidden in her gown (today this dress is in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.)

Alva Vanderbilt as “Electric Light” (Jose Maria Mora.) Right: the dress today at the Museum of the City of New York.

At two in the morning the revelers ascended to the third floor gymnasium, which was converted into a forest of palm trees draped with orchids. There they dined on a feast prepared by Delmonico’s, including lobster, terrapin, oysters, and a rapturous dessert called Macedoine of Fruit in Champagne Jelly. More dancing ensued, until the exhausted guests exited onto Fifth Avenue in the early morning, shocking local children on their way to school.

Macedoine of Fruit in Champagne Jelly.

Newspapers across the country reported the most minute details of the evening’s festivities, transforming it into legend. The Vanderbilt Ball was the most widely-discussed gathering in the city’s history! That is, until 14 years later, when the Astors fought back to regain party prominence.

Coverage of the Vanderbilt Ball in The New York Journal, 1883.

Waldorf vs. Astoria

William Waldorf Astor’s palatial home was next door to his aunt Caroline Astor’s mansion on Fifth Avenue at 34th Street. But their relationship was anything but neighborly.

When William married an “ordinary” woman, Mary Dahlgren Paul, the couple were no longer invited to Aunt Caroline’s soirees featuring “The 400” (the number of people who could fit in her ballroom.) Angry William decided to get retribution by demolishing his home and replacing it with a 13-story hotel called The Waldorf, blocking the views and sunlight from his Aunt’s next-door mansion and garden, and attracting dreaded “transients” into the city’s most exclusive residential neighborhood.

The new Waldorf Hotel (left) dwarfs Caroline Astor’s home, photo 1893.

The combined buildings create the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, photo 1900.

Caroline fought back, turning her mansion into a hotel as well, naming it The Astoria. The two hotels competed with each other for a few years, until the Astors decided that money was thicker than blood, and joined the two hotels together to form the fabled Waldorf-Astoria. They also constructed a 3,000-foot walkway along 34th Street for their wealthiest patrons to parade in front of gaping throngs of gawkers. This gilded passage was known as Peacock Alley, home of the original “red carpet” and “velvet rope,” used for all swanky functions till this day.

Peacock Alley

The Waldorf-Astoria was demolished in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building, and opened its new quarters at Park Avenue and 50th Street in 1931. But the original Waldorf was the setting for the most spectacular and controversial gathering ever seen in Gotham.

The Bradley-Martin Ball

Seeking to surpass the Vanderbilt Ball, Bradley Martin and his wife Cornelia Bradley-Martin decided to transform the Waldorf-Astoria into the Versailles of Louis XV to create the most over-the-top costume party in the city’s history. Its date of February 10, 1897 was announced well in advance, giving the 700 invitees enough time to have their costumes made and their jewels polished.

Fifty florists provided the decor, which included thousands of roses, hurled at the tapestry drapes and allowed to rest where they fell, a most unusual effect. 6,000 mauve orchids and fragrant clematis grew amongst woodland bowers, sylvan dells and “flirtation nooks.” Several orchestras were hired to fill the ballrooms with melodies.

To say that the elaborate costumes did not strictly adhere to the theme of 18th-century France is an understatement. There were colonial Dutchmen, an Algonquin chief, several George Washingtons, Mary Queen of Scots, musketeers, toreadors, court jesters, Romeos, Juliets, a Cleopatra, a Pocahontas, and many Marie Antoinettes. The city’s available supply of shoe buckles, snuff boxes and fobs was cleaned out, and priceless heirloom jewels were released from private vaults. One young artist created a sensation as a falconer, bearing a giant stuffed falcon on his shoulder, and wearing pants so tight they left little to the imagination. At midnight the guests gathered to dine on suckling pig and champagne, then continued dancing until dawn. (Select to enlarge:)

At a time when crusading journalists like Jacob Riis were exposing the plight of New York’s poorest denizens, the Bradley-Martin Ball created quite a stir. Rumors that anarchists planned to bomb the event caused Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt to surround the Waldorf with his force, while detectives, outfitted in period costumes, patrolled the interior.

The final bill was over $350,000 in 1897 money. The final cost to the lives of the hosts was much higher. Ministers denounced the pomp and pride of the rich. Social reformers proposed alternative uses for the money spent. Newspapers thundered with scathing editorials. Instead of launching them to the top of society, The Bradley Martins found themselves outcasts in their own city, and fled to Europe, never to return. But if you think their ball marked the end of the Big Apple’s over-the-top parties, think again.

The Bradley-Martin Ball as covered by “The New York Journal,” 1897.

The Beaux Arts Ball

This 20th-century costume party deserves a mention, due to its Gotham-centric attire. In 1931, in the midst of the Great Depression, attendees were charged $15 each to enjoy a setting described as “modernistic, futuristic, cubistic, altruistic, mystic, architistic and feministic.” Hosted by the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects in the Hotel Astor, the fame of this gathering has endured, due to a certain photograph.

The picture shows the city’s most famous buildings as costumes, worn by the architects who designed them. From left to right, we see A. Stewart Walker as the Fuller Building, Leonard Schultze as the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Ely Jacques Kahn as the Squibb Building, William Van Alen as the Chrysler Building, Ralph Walker as 1 Wall Street, D.E. Ward as the Metropolitan Tower, and Joseph H. Freelander as the Museum of the City of New York. The event, covered by WABC radio, was declared by the New York Times as “one of the most spectacular parties of the century.”

The Dinner on Horseback

New York’s exclusive Equestrian Club expected incoming presidents to host a lavish party. In 1903, new president C.K.G. Billings outdid himself. As a ruse, he invited several dozen members of the club to attend “a quiet evening at Sherry’s” (a popular NYC dining spot.) Little did these guests know what they were in for.

Upon entering, the members were gathered in a small banquet room, which showcased an actual stuffed horse as the centerpiece. After consuming oysters and caviar, the unsuspecting guests were led to a larger dining room, which had been transformed into an English country estate. Grass covered the floor, burbling brooks flowed through lush meadows, and vine-covered cottages set the scene.

There, encircling the room, were dozens of live horses, which Billings had arranged to be led over from his stables, their hooves covered with cloth to protect the restaurant’s floors. Waiters (dressed for a fox hunt) invited the guests to hop atop the horses. It was there that they ate their dinners from tray tables attached to the saddles, and sipped champagne through long straws leading to bottles in their saddlebags. While the horses contentedly munched on oats (and relieved themselves) the human diners were entertained by a series of variety acts.

Newspaper reporters had a field day. When photos of the bizarre event were printed, Billings was roundly mocked for his expression of heedless wealth while thousands of New Yorkers starved. The Horseback Dinner became a symbol of the excesses of the idle rich.

A peephole candy egg (normal size).

The Giant Egg Dinner

One unnamed New York hostess had an unusual fondness for Parisian “peephole” candy eggs, and was determined to actually host a dinner party inside of one! So she hired artisans to construct a canvas egg large enough to accommodate sixty people for dinner. Unfortunately, the importance of ventilation had not yet been studied. Halfway through the entree the company began dropping like flies. The evening had to be cut short as oxygen-starved victims choked and crawled their way out of the giant egg, into their waiting carriages, and then home to sleep it off. So much for extravagance.

The Barnyard Party

Elsa Maxwell delighted society by holding silly, child-like gatherings for childish grown-ups. Her ultimate event was the infamous Barnyard Party, held in the Waldorf’s fancy Jade Room. She filled the place with fake apple trees (complete with sewn-on apples), a beer “well” with working bucket, bales of hay, ten huge live hogs and three cows (two were real and gave milk, the other was constructed of paper mâché and gave champagne.) At the height of the festivities Elsa’s hired hog caller from Ohio created a huge stampede to the delight of the blue-blooded guests, which included the Astors and the Vanderbilts. All had to dress like farmers and milkmaids. Mrs. Ogden Mills wore a diamond tiara with her denim overalls. The party was deemed a fantastic success.

The one and only Elsa Maxwell.

More Crazy Dinners

Delmonico’s Restaurant was the scene of dozens of gastronomic festivities. Perhaps the most memorable was the Swan Banquet of 1873, when wealthy importer Edward Luckemeyer handed ten grand to Lorenz Delmonico and requested a memorable dinner. It was memorable, indeed. A massive oval table filled the expansive ballroom; at the center was a thirty-foot lake surrounded by a landscape of flowers. One reporter noted, “There were hills and dales, violets carpeting the valleys, and tiny blossoms covering miniature mountains.” Floating serenely in the lake were four swans borrowed from Prospect Park, kept within a floor-to-ceiling gold cage crafted by Tiffany. Only the edge of the table was left free for plates. All went well, although the raucous mating of two of the swans made conversation difficult.

Another wacky dinner was hosted by the inimitable Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish. Known for her insulting repartee, she once gave a dinner party in honor of a monkey. This event became the talk of the town, inspiring another hostess to persuade her canine-loving friends to dress as maids and serve dinner to their pets, which were seated at a big banquet table. Another dowager invited her guests of honor to attend a luncheon, bringing their favorite dolls to dine beside them.

Delirious Dining

New York’s restaurateurs have always been a competitive bunch, eternally vying with each other to attract hungry patrons. The lengths they went to resulted in extraordinary menus and shocking repasts.

The inventor of extreme feeding was one William Niblo, who opened the Bank Coffee House in 1840, and later the popular Niblo’s Garden, commandeering an entire city block at Broadway and Prince Street. Ever in search of rare comestibles, his staggering menus included “Bald Eagle shot on the Grouse Plains of Long Island,” “a remarkably fine Hawk and Owl shot in Hoboken,” and “Buffalo Tongues from Russia.” Diners would recoil in delight when Niblo announced, “Clear the passage! Here comes the Bear!” And sure enough, a huge bear, smoking hot, would be served up whole and standing.

As I explained in the Meat Chapter, New Yorker’s’ favorite meal was beef. A beefsteak dinner was the best excuse for the rich to “go slumming.” Enjoying a thrilling descent into savagery, wealthy patrons would sit on sawed-off barrels and chow down on massive steaks, served atop upturned crates. No knives or forks were available, only a thick towel to wipe off the slobbering juices.

Beefsteak dinner at Reisenweber’s. (Library of Congress)

The premier beefsteak garret was Reisenweber’s on Columbus Circle. When Sir Thomas Lipton, the tea magnate, visited the city in 1906, he was ushered into the eatery, which was decorated in a nautical theme to celebrate Lipton’s triumph in the America’s Cup. While seated on a beer barrel, waiters dressed in sailor suits descended from the ceiling on ropes, serving Lipton his beefsteak on top of an empty champagne case.

“Turtle Independence Day,” 1922. (Saveur)

Turtle Mania

Beef’s chief competitor for New York’s insatiable appetite was none other than turtle (a.k.a. tortoise or terrapin) as in Turtle Soup. People went absolutely mad for this delicacy, from colonial days to the early 20th century. Native to the Caribbean, turtles could weigh several hundred pounds. When a restaurateur was lucky enough to procure one, he would take out ads in the newspapers, trumpeting, “A mammoth turtle will be cooked in the best style on Wednesday next...the lovers of good eating will have their taste gratified” and “Turtle Soup, worthy of the animal of which it was made.” Dining showman William Niblo would set a live turtle onto the sidewalk, upside down and legs wriggling, to entice passersby. Today, few remember and fewer serve turtle soup.

“Evening Post,” 1812.

The only food New Yorkers loved more than turtles or steaks was their favorite bite for centuries: the oyster (the city was surrounded by them.) Read all about this superstar bivalve in the Oyster Chapter.

New York Goes Vegetarian?

By the 1800s, vegetarian foods were nothing new in New York. Jewish “dairy” restaurants were flourishing; they offered no meat, and concocted unusual edible inventions such as vegetable loaf, protose (made from wheat and peanuts) and other meat substitutes. But Jews ate meat as well, just not at the same time as dairy.

Leave it to Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, his patient C. W. Post, and Reverend Sylvester Graham to urge totally meatless dining. They waged war against steaks, fried foods and pies, and brought about a revolution in the American breakfast, which had always featured meat. Today’s morning meal of cereal, oatmeal and fruit owes its origins to these anti-meat warriors.

Sylvester Graham

Graham came to New York in 1833, inspiring the “temperance boardinghouse.” His dietary principles were institutionalized, inspiring more vegetarian hostelries which survived until the late 19th century, drawing fans like Horace Greeley, William Lloyd Garrison and Gloria Swanson. At the same time, scientists were discovering the mysterious vitamin and the calorie, in an effort to understand the widespread scourge of stomach ulcers.

The New York Vegetarian Society was founded in 1852, and offered impressive menus at exclusive dinners held in major hotels. They opened the city’s first vegetarian restaurant, unimaginatively named Vegetarian Restaurant Number One, on 23rd Street. No food was served that required the destruction of life, including all meat and fish. By 1900 vegetarian restaurants like The White Rose and The Laurel were operating successfully. Today, vegetarian, vegan and raw food eateries are thriving.

Menu for The Laurel, 1904.

Capsular and Tabloid Restaurants

Okay, sometimes things got out of hand, like capsular restaurants, where the food was served in pill form. Imagine your dinner plate arriving at your table, containing 3 pills! This led, in 1901, to the first tabloid restaurant, where the food was compressed into tiny tablets (another brilliant idea by Kellogg and two guys from the pharmaceutical industry.) The tabloid eatery on Fulton Street in Brooklyn offered “compressed beefsteak.” Customers were enchanted with the tabloid concept, often dissolving their meal in a cup of hot water and drinking it like coffee.

Fun Feasting for Bohemians

By the early 20th century, Greenwich Village swarmed with poor painters, sculptors, radicals, suffragettes and revolutionaries. These anti-establishment types had to eat as well, so inventive restaurateurs created a plethora of silly, absurd eateries, each vying with one another to attract the intellectual rabble.

For example, at the popular Pirate’s Den on Sheridan Square, guests would be greeted by a pirate, complete with eye patch, cutlass, and shoulder-sitting parrot. The atmosphere included treasure maps, a dead man’s chest, and jazz bands performing on the decks of three pirate ships. Newspaper reviewers dubbed it “the most colorful, fairy-tale-ish place in the Village.” NYC Mayors would often eat Thanksgiving dinner there! (Select to enlarge:)

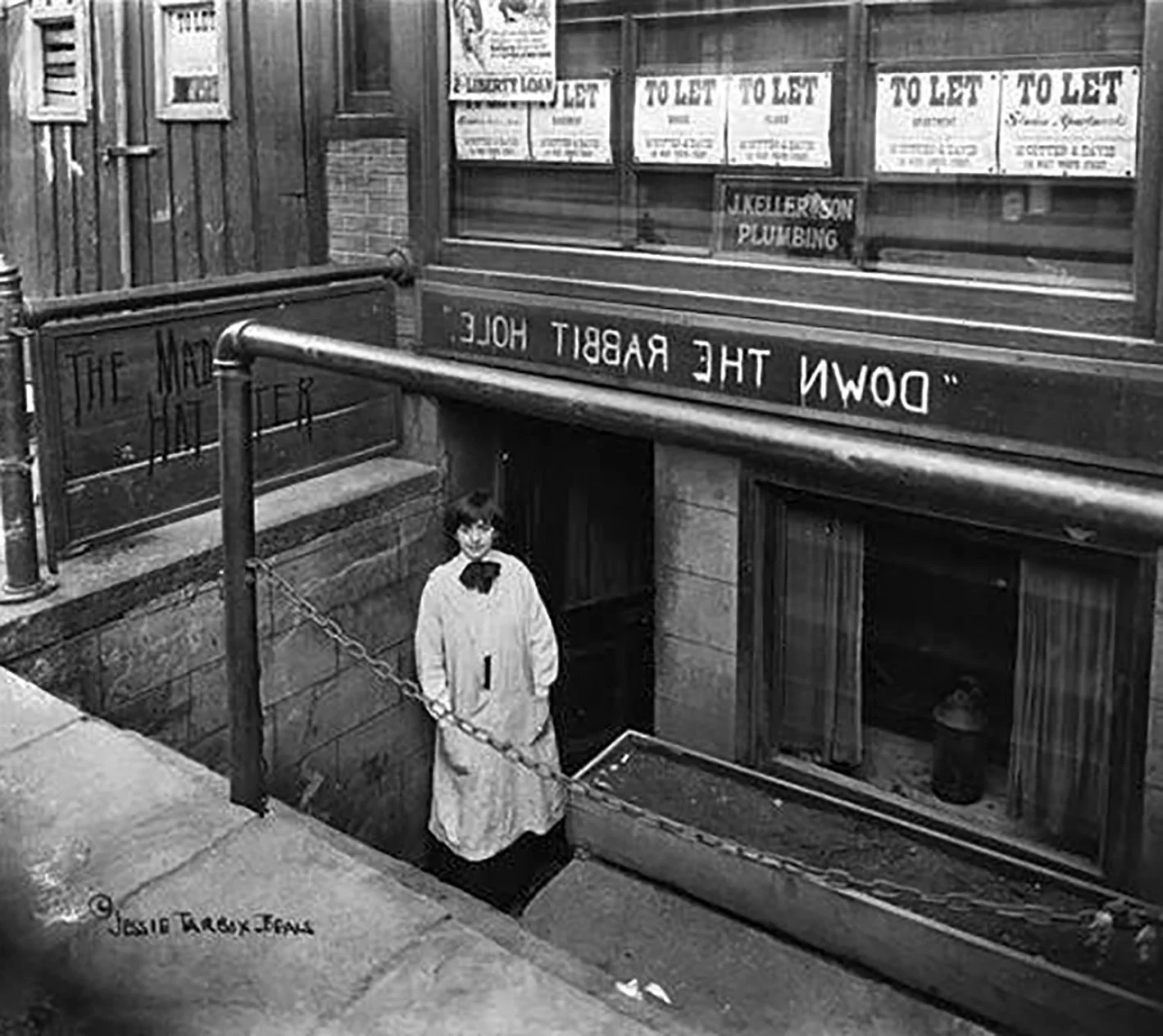

To enter The Mad Hatter, in a basement on West 4th Street, one had to descend through a “Rabbit Hole.” The Crumperie offered crumpled foods like squished eggs and sponge cake. At the nearby Pepper Pot you’d be accosted by Tiny Tim, a bizarre character who sold “soul candies,”each one wrapped in one of his poems. At The Blue Horse diners ate in stalls and the orchestra wore blinders.

One of the most popular haunts was The Village Barn on 8th Street, where patrons square-danced, waiters yodeled, and turtle races were held nightly. A global clientele streamed into Polly’s, run by radical Polly Halladay, whose husband, Czech anarchist Hippolyte Havel was the chef, turning out amazingly excellent food. Unknown artist Stuart Davis painted the sign outside.

All this insanity didn’t last long. As Greenwich Village’s fame grew, the stockbrokers and wealthy “slummers” showed up, laughing and staring at the Villagers as if they were animals in the zoo. And that was the end of “Bohemia.”

The Healing Feast

A more modern-day example of food experimentation occured a couple of months after the September 11, 2001 disaster. Two creative chefs, Paul Liebrandt and Will Goldfarb, organized an event at the Village restaurant Papillon, which caused quite a sensation. It was an “interactive” dinner, where the guests were requested to follow the chefs’ directions when consuming the courses. They consequently found themselves feeding one another lobster tartare while touching silk and sandpaper. Then they were blindfolded, their hands tied behind their backs, to bob for urchin ravioli floating in soup.

The increasingly amazed guests were next taken into a foggy room to slurp banana jelly from the hips of a reclining, latex-clad figure. They were given drinks with soft “ice cubes” in them, which they had to swallow whole. The cubes were made of onion sorbet, to enrich the flavor of the following dish, cheese served on a mousetrap. Dessert was chocolate soup sucked from baby bottles. The meal lasted over four hours.

Somehow, the sharing of a meal in the most intimate ways, touching and feeding one another, moved the guests even more than the chefs anticipated. Many found joy and a bit of release from the harrowing experience of 9/11 which they recently endured.

It seems New Yorkers will try just about anything to chow down on a good time.

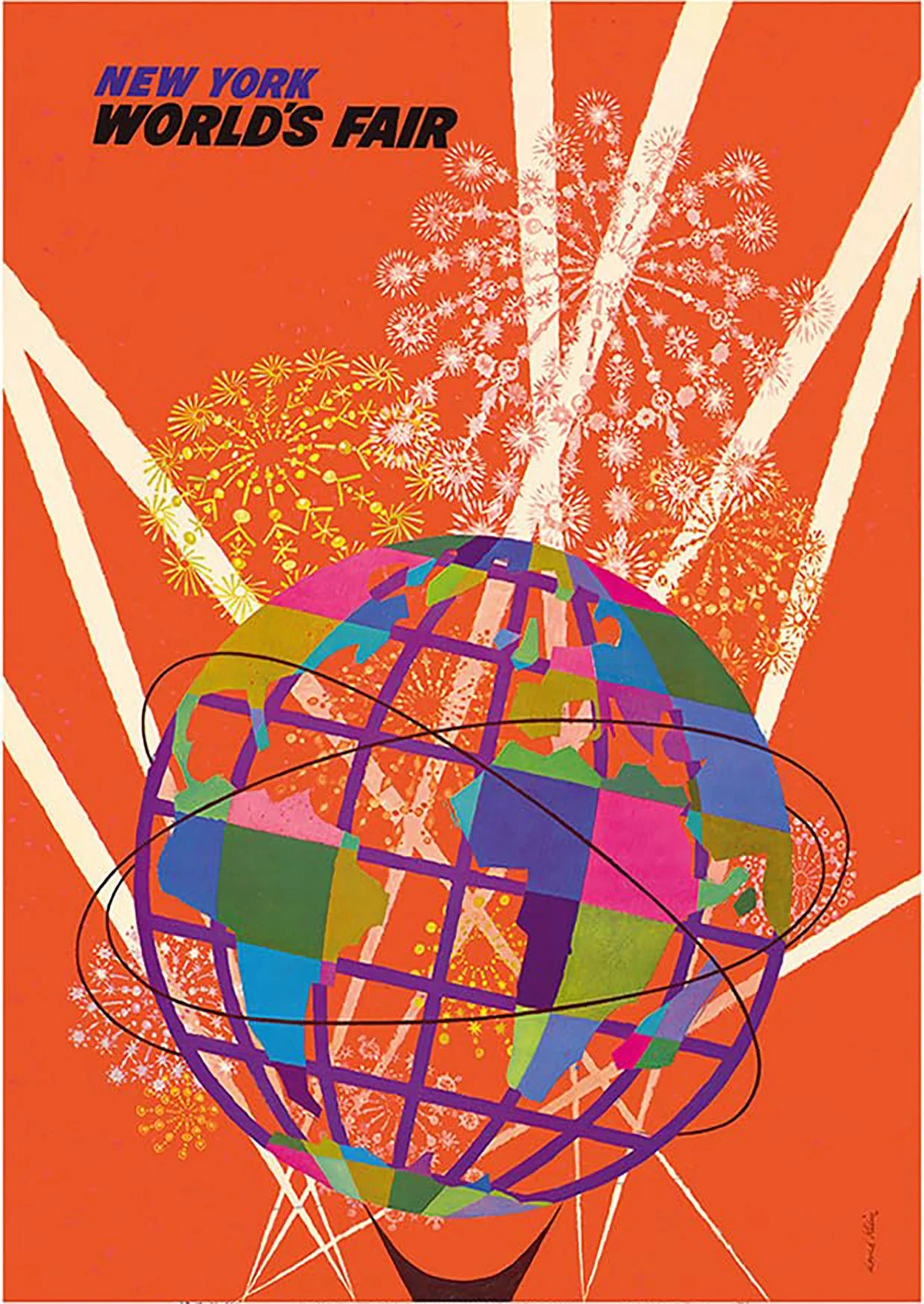

Next Up on NYC EATS

We’ll take a look at the gastronomic offerings of the two New York World’s Fairs, and their surprising transformation of America’s tastes and dining choices. Meet you at the Fairs!